Some charities have addressed the issue of gender equality. A lot has been achieved. But there is still a long way to go. A glance at the membership of boards of trustees is enough to show that women are still underrepresented.

‘Women have achieved so much – and there’s still so much to do!’ says Rita Schmid. She is chair of the board of trustees at the Foundation for Research into Women’s Labour (Stiftung für die Erforschung der Frauenarbeit), founded in 1960. The foundation was made possible by the proceeds from the second Swiss Exhibition for Women’s Work (SAFFA) in 1958. The exhibition was organised by various different women’s groups and their umbrella organisation, and addressed the role of women in modern society. In addition to family responsibilities and volunteering, women also wanted to be part of the professional workforce.

The SAFFA 58 exhibition also served as a kind of publicity event for women’s suffrage. Their efforts remained unsuccessful in this respect, however – Swiss men rejected the proposal yet again in a vote in 1959.

Women’s labour

‘The charity’s formation made a strong statement, however: that female labour is a multi-faceted area of investigation,’ asserts Rita Schmid, adding that the board of trustees was made up of active campaigners for women’s suffrage. This was finally granted in 1971. Rita Hermann-Huber sees the fact that it took more than ten years after SAFFA 58 before women were given political rights as a reflection of the gender roles that prevailed in that period. ‘I’m sure that at the time, SAFFA 58 did not find favour with many men, and indeed some women. Women belonged in the kitchen and with the children,’ says the president of the Foundation for Civic Education and Training (Stiftung für staatsbürgerliche Erziehung und Schulung). This organisation, too, was founded from the proceeds of the exhibition. The charity dedicated itself to preparing women to take up their civic responsibilities. It aimed to deepen women’s understanding of the work that needed doing in the wider community. Many things have improved since then. Since the introduction of women’s suffrage, Hermann-Huber has seen major political changes.

‘Which I’m thankful for,’ she says, but adds: ‘Equality has not yet been achieved at all levels, however. The gender pay gap and balancing work and family life are still problematic areas.’ Action is still needed. And this is what guides the charity’s work. It aims to support projects that contribute to gender equality. The foundation is able to offer financial support to 25–30 projects each year. It doesn’t carry out any projects itself, however. ‘Our foundation generally receives funding applications from women’s organisations,’ says Hermann-Huber. In recent years, she has seen a change in the kind of applications they receive. There are an increasing number of projects aimed at migrant women. Violence against women is another topic that has become more prominent, alongside gender issues. ‘When the women’s strike took place, we received a funding application for a book with portraits of strikers, for example,’ she recounts. However, the foundation only supports book projects if they are published by women’s organisations or groups. Many organisations are currently planning events to celebrate the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage. ‘Many of the project proposals we’ve received show that the question of gender equality is still a relevant one,’ says Hermann-Huber.

Positive polarisation

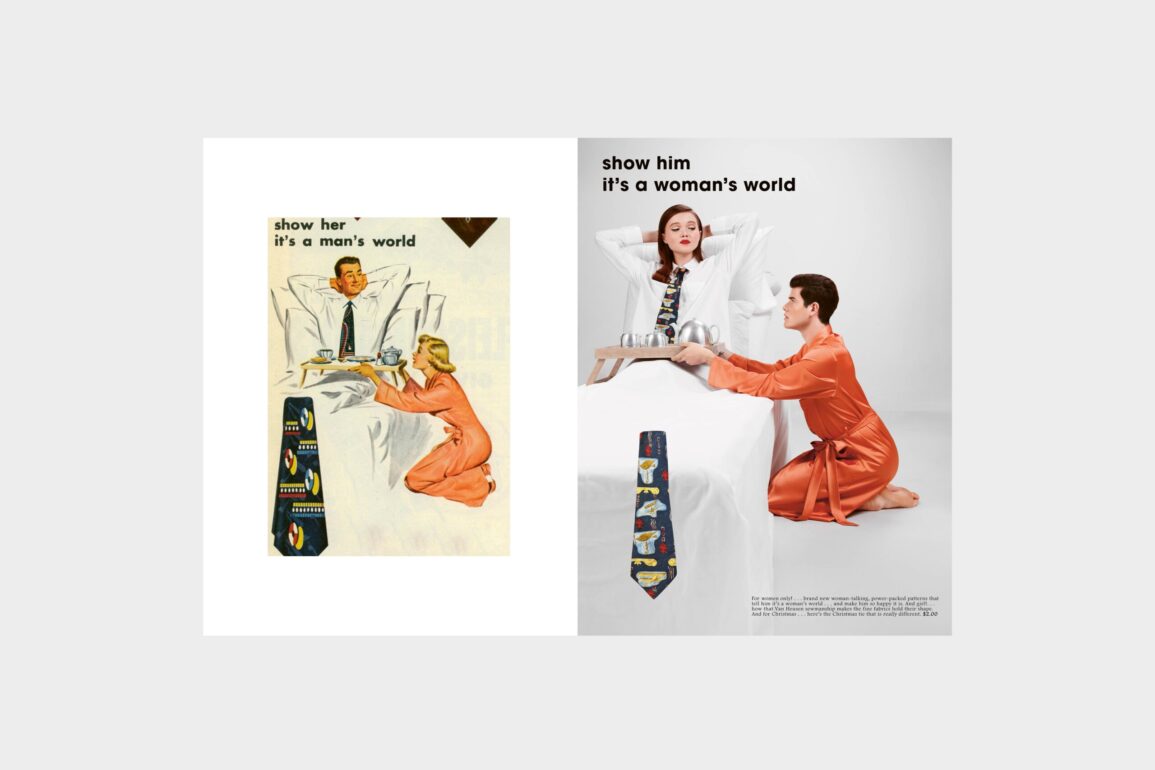

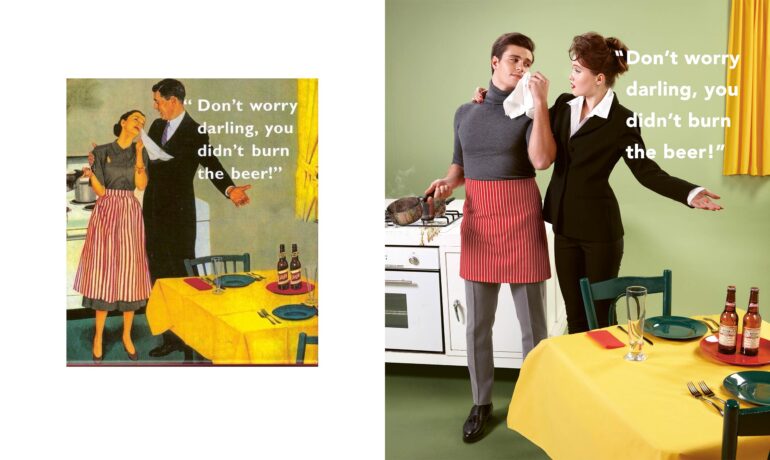

Women faced many hurdles, both in terms of their political rights and work. They had to fight for everything. When women stood up for their rights, a common criticism was that it led to social divisions. ‘The women were put back in their place. Major topics like a financial crisis and alleged external threats to Switzerland were given prominence to protect the principle of unity,’ explains Franziska Schutzbach. Schutzbach is a sociologist and gender researcher, and considers the same issues to be relevant today: ‘We need courage and, above all, an understanding that conflict, contention and polarisation can also be good and important things.’

This is especially true when it comes to gender equality issues, which can be very polarising. But then the prevailing cultural consensus has always overpowered the women’s movement, says Schutzbach. Because women had no political rights, women’s associations and organisations were a key force. And these channels still provide support today. Parliamentary policy alone is not enough, asserts Schutzbach.

We need civil society, people out on the streets and organisations like charities. Schutzbach wishes that the latter would ‘act with a little more courage in this area.’ In particular, she feels there is a lack of charities that advocate for gender equality at a higher level and with a clear political agenda. Schutzbach is working to establish a feminist institute to carry out gender research and share the knowledge with the wider public. The aim is to carry out meaningful, socially relevant and politically active research. The methodology and culture of the institute will be different to that of a traditional academic institution. The focus will not be on publications and professorships, but on generating knowledge for a more emancipated society. In Germany, party-affiliated foundations such as the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung are engaged in political educational work – but Switzerland lacks equivalent institutions. Critical knowledge remains purely academic and rarely finds its way into wider society, in part because many people leave school at 16 or undergo highly practical professional training. Yet political education and individuals’ capacity for critical reflection is essential, particularly in a direct democracy.

Impressive women

But there have always been women who put themselves out there. And men who acknowledged them. This was reflected in the creation of the Irma Landolt-Lechner women’s foundation in 1974. The author and women’s activist Meta von Salis-Marschlins made an impression on Karl Landolt. ‘She impressed him because she refused to be forced into the female role society had placed upon her,’ says chair of the board of trustees Ariane Bolli-Landolt. Karl Landolt enjoyed a partnership on equal terms with his wife Irma – who raised four children in addition to working at the school. ‘They had clearly defined roles, but these were considered of completely equal value,’ Bolli-Landolt explains.

It was only logical that Karl Landolt, former headmaster of a school for girls, went on to create a foundation dedicated to advancing the rights of women. ‘It is an expression of honour and respect for women in general, and for his partner Irma Lechner and single mother Marie Landolt-Übelmann in particular,’ says Bolli-Landolt. A man also played a role in the foundation of the Elisabethenwerkstiftung. ‘At the time and in that generation, it was progressive for a man to set up a foundation that supported women’s projects,’ says trustee Rosmarie Koller-Schmid. Karl Hompesch founded the Elisabethenwerkstiftung in 2003. As a Catholic, he was familiar with the story of Saint Elizabeth, who helped the poor. He was also acquainted with the Elisabethenwerk organisation run by the Swiss Catholic Women’s Federation (SKF). ‘Of course, he could have just left a bequest to the Elisabethenwerk organisation,’ says Liliane Parmiggiani, fundraiser for Elisabethenwerk. But he wanted the money to go directly to the projects run by the Elisabethenwerk. The Elisabethenwerk supports women in Uganda, India and Bolivia and helps them find their way out of poverty, whatever their religious and ethnic background. Local project staff work with women affected by poverty to develop opportunities for earning their own income, share knowledge about hygiene and family planning and do preventive work against trafficking and domestic violence.

The Elisabethenwerk’s projects also involve boosting women’s self-confidence. The Elisabethenwerk presents a progressive image of women – which some might find surprising given the Catholic context. This is down to the SKF, with which it is affiliated, and which is the largest religious women’s umbrella organisation in Switzerland. ‘There is a Catholic Church that exists outside of the official church institution,’ explains Parmiggiani. ‘People are always positively surprised by how progressive the SKF is.’ This is clearly reflected in the federation’s work promoting equal rights for women within the Catholic Church, and in the gender equality issues relating to marriage supported by the federation’s board.

The Elisabethenwerk, on the other hand, focuses on sustainable development work with women affected by poverty. ‘Many women are concerned about environmental sustainability,’ says Koller-Schmid. The aim was never merely to provide financial resources but to give women the opportunity to find their way out of poverty and gain independence by teaching them new skills. It’s about helping women to help themselves. The goal is for the impact to be felt beyond the individual projects. The question of resources remains key. Without this, social and legal equality will never be achieved. Earning their own income improves women’s social standing.

‘In order to have the courage to demand their rights, women need empowerment and a financial foundation,’ says Parmiggiani. ‘In other words, work.’ The same applies in Switzerland.

What is work?

Franziska Schutzbach also highlights the significance of work as a symbol of equality. She observes that a lot has been achieved since the first women’s strike. Today, the majority of women are in employment. But it remains a tricky topic. Many women work part-time, and suffer disadvantages in their career and reductions in their pension as a result. ‘Employment is often first and foremost about adapting to the male environment,’ says Schutzbach. ‘If being part of the capitalist production process is the only measure of success, I think that’s a pretty sad vision of emancipation.’ Inequality and discrimination remain major issues. Women who work still continue to shoulder the burden of household chores and family duties. ‘Women in Switzerland have always had to fight hard for their place,’ says Schutzbach. Many developments came late in the day. Marital rape only became an offence prosecuted ex officio in 2004. Maternity leave was only introduced in 2005. ‘The fact that we are still fighting for equal pay and demanding governmental measures is sometimes called a kind of dictatorship,’ says Schutzbach. ‘But it’s the opposite. Opposing discrimination and inequality is a sign of democracy, and is a constitutional obligation. The government is responsible for ensuring equal pay and taking action.’ Rita Schmid also laments the continued existence of the gender pay gap – and looks to the future: ‘Digitalisation in the workplace raises new questions that need to be addressed from a gender perspective.’ At the Foundation for Research into Women’s Labour, this current dimension is just as important as historical analysis. On the one hand, the foundation wants to highlight women’s achievements in the collective historical and cultural memory of an enlightened society. On the other, it wants to encourage critical examination of current working conditions in environments with an above-average proportion of female workers, such as the care sector and retail. ‘Equality and work are closely interwoven,’ says Schmid. This starts with how ‘work’ is defined and what is considered ‘work’. If an activity contributes to society, it should be recognised as work and remunerated accordingly. ‘We know that there have historically been, and continue to be, major differences in the assessment of performance, pay, career trajectories, work-life balance and employment opportunities from a gender perspective,’ says Schmid. ‘Despite significant progress in recent decades, women are still subject to widespread discrimination in terms of the respect and appreciation accorded to the work they perform.’ Ariane Bolli-Landolt shares this view: ‘It’s no secret that women make a huge contribution, not only within their own families but in terms of caring for (sick) relatives, volunteer work and sociocultural projects. They receive nowhere near enough recognition for this, let along getting paid.’

Diversity does good

To make sure the topic of gender is given sufficient consideration within the organisation, the Kyria umbrella foundation has enshrined it in its statutes. Tanja Bootz and Brigitt Küttel founded Kyria in 2019. It is the first umbrella organisation that expressly aims to involve and empower women. ‘We care about addressing these issues,’ says managing director Küttel. ‘Diversity does so much good and is so valuable,’ adds Bootz. The topic figured prominently in Küttel’s youth. Gender equality was discussed around the dinner table. Küttel was eight years old when women were given the vote. She still remembers it as an important moment. ‘When my mother Elisabeth Kopp was asked to become a member of the Municipal Council, the topic became even more significant – she couldn’t very well fight for something for years and then turn down the candidacy.’ Today, former Federal Councillor Elisabeth Kopp is a member of the Kyria board of trustees. In her honour, and because of the importance of the issue, the umbrella foundation formed the Elisabeth Kopp fund for the advancement of women. Its first project was to initiate and finance a database containing over 200 foundations from across Switzerland dedicated to supporting women and women’s projects. The decision to play an active role was made in the early days of Kyria. ‘We decided in the first meeting of the board of trustees that we didn’t just want to create funds and make donations to causes and topics that were brought to our attention. We wanted to be active ourselves and make our values felt,’ says Küttel. The Kyria umbrella organisation actively opens its own funds for this purpose. In doing so, it wants to give small-scale donors the opportunity to get involved in, and support, these issues and values.

Increasing visibility

‘While the topic of gender is important, we don’t want to be pigeonholed,’ says chair of the board of trustees Tanja Bootz. They want to be active in the areas that matter to them and get involved in a variety of different ways. Which is why the board of trustees has a diverse membership. By contrast, the board of trustees of the Irma Landolt-Lechner women’s foundation is made up entirely of women. This is not a formal requirement. ‘It’s become a kind of unwritten rule,’ says Ariane Bolli-Landolt, however. ‘I don’t see it as a prerequisite for doing good work, but I really value nominating our female prize winners as part of a purely female committee.’ The foundation presents awards to women who have done outstanding work in the cultural or social sector. Bolli-Landolt feels that raising the profile of these achievements is more important than having a balance of genders on the board of trustees. Women are still in the minority on boards of trustees in the Swiss charity sector as a whole. The Stiftungsreport 2020 (for 2019) listed a total of 12,763 chairs of boards, of which only 20.4 percent were women. The proportion of women among the 61,106 board members more generally was slightly higher at 27.9 percent. At an executive management level, women made up 34.4 percent. With these figures in mind, Brigitt Küttel asserts that there is still a lot of work to do in the charity sector, as well as in society at large. ‘We are seeing more and more women becoming increasingly assertive, however,’ adds Bootz. ‘Women also increasingly have their own money, and are wanting to use it to make a difference.’ Both women are sceptical about introducing quotas to boost the representation of women. ‘We’re not sure a mandatory quota is the best idea,’ says Küttel. ‘The most important thing is still having the best qualifications for the position in question and, in the case of charities, an interest in the topic. However, a quota can at least encourage people to make more of an effort to appoint women to executive bodies and committees, and that is definitely a positive thing.’ Franziska Schutzbach is not a big fan of quotas either, even though she would definitely support them. ‘If we need a quota, it indicates that a lot of other things are wrong,’ she says. ‘It isn’t enough just to put a few more women on committees.’ What matters is for charities to actively engage with gender issues. There is usually a gender aspect to most topics. Organisations may need to consult external experts to help explore these questions – how is gender equality linked with the environment, for example? Or arts funding? ‘Of course, this might involve appointing more women to management positions within your foundation,’ says Schutzbach. ‘But it is often the case – and research is being done on this – that when male-dominated organisations get involved in gender equality issues, these organisations generally become more responsive to these topics themselves within their own structures, and over time will naturally appoint a more diverse staff.’