Whether part of an international movement or focusing on long-standing projects in Switzerland, foundations drive sustainability and help promote environmental awareness.

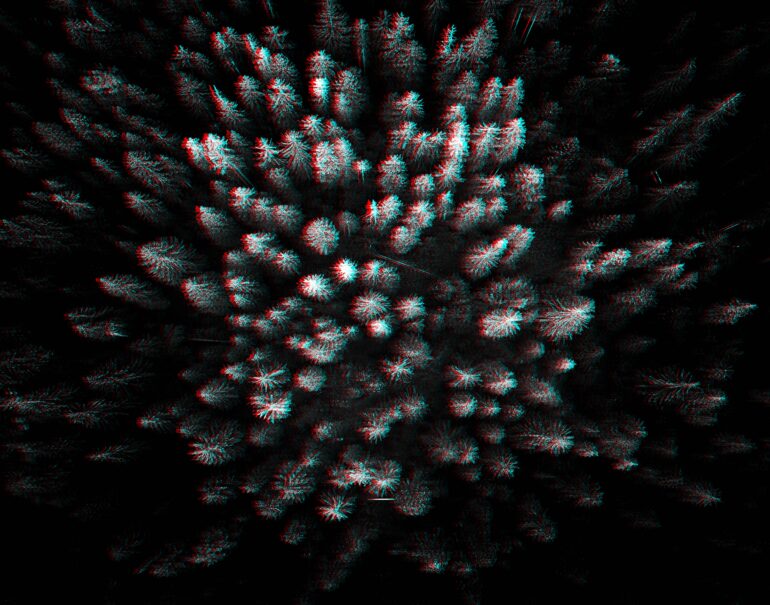

The ambitious goal is to plant one trillion trees worldwide. ‘If we succeed, it will help secure work for around 350 million people around the world – particularly in developing countries,’ explains Marianne Jung, who, together with Pirmin Jung, set up the Plant-for-the-Planet Switzerland foundation in 2016. ‘The trees will help restore the soil’s fertility, biodiversity will return and there will be a positive impact on the local climate. They store large quantities of CO2 and offer us a lifeline of up to 15 years to achieve the 2‑degree goal,’ explains her foundation partner. The idea behind the foundation was originated by German environmentalist Felix Finkbeiner. As a 9‑year-old in 2007, he called on children to plant a million trees.

According to the international Plant-for-the-Planet movement, this goal was achieved in 2010. The follow-up Trillion Tree Campaign was launched in 2011. In 2019, a study by the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich also came to the conclusion that reforestation can be a powerful tool when it comes to saving the climate, but pointed out that time is pressing, as new forests will take decades to mature and achieve their full potential as a source of natural carbon storage.

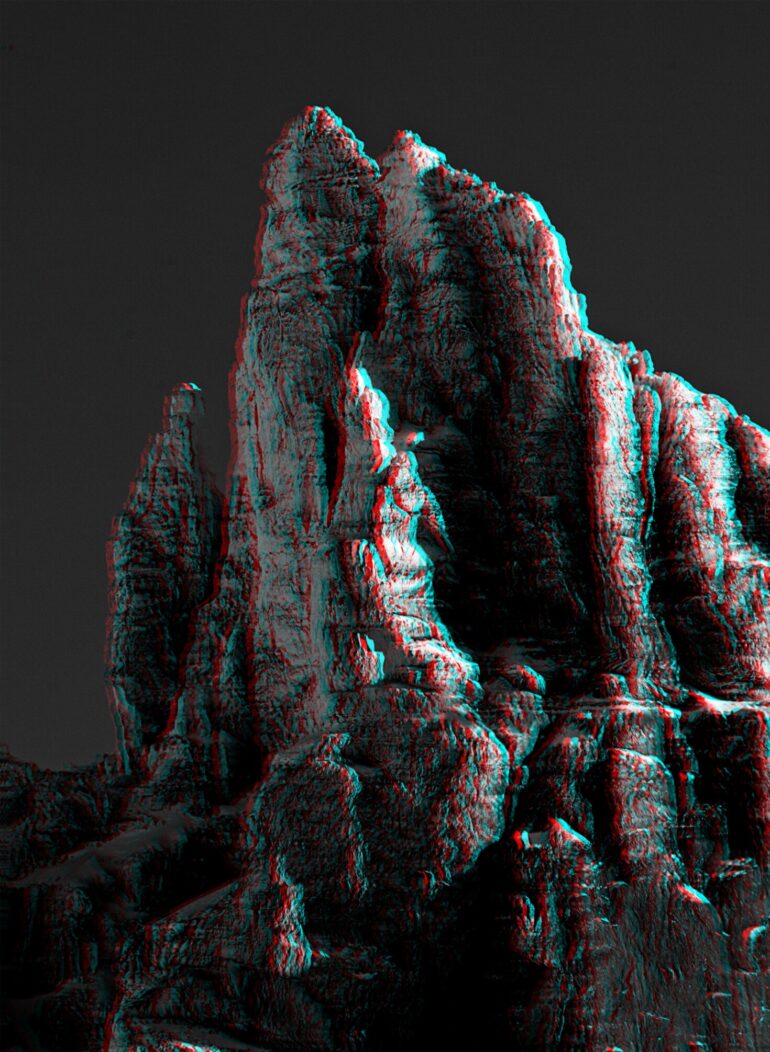

Protection forests are vital

Trees shape our landscapes, cities, meadows and mountains. They became the focus of environmental debate in the 1980s in the wake of deforestation and forest dieback. ‘That was the trigger,’ states PR manager Dunja L. Meyer, describing the origins of the Bergwaldprojekt 1987 foundation. ‘Deforestation and forest dieback became a growing concern.’ A small group emerged. They were keen to take action rather than simply discussing the issues and went to work in the forest. The Bergwaldprojekt (Mountain Forest Project) was born. Through its work, the foundation aims to show people the benefits of conservation. ‘It is probably true to say that there is no such thing as totally selfless conservation,’ claims Dunja L. Meyer. The mountain forest has a whole range of functions that benefit people: it serves as a protection forest for the mountain region and its flood control effects extend as far as the lowlands. It absorbs CO2 and provides wood as a construction material. And it is home to a diversity of plants and animals.

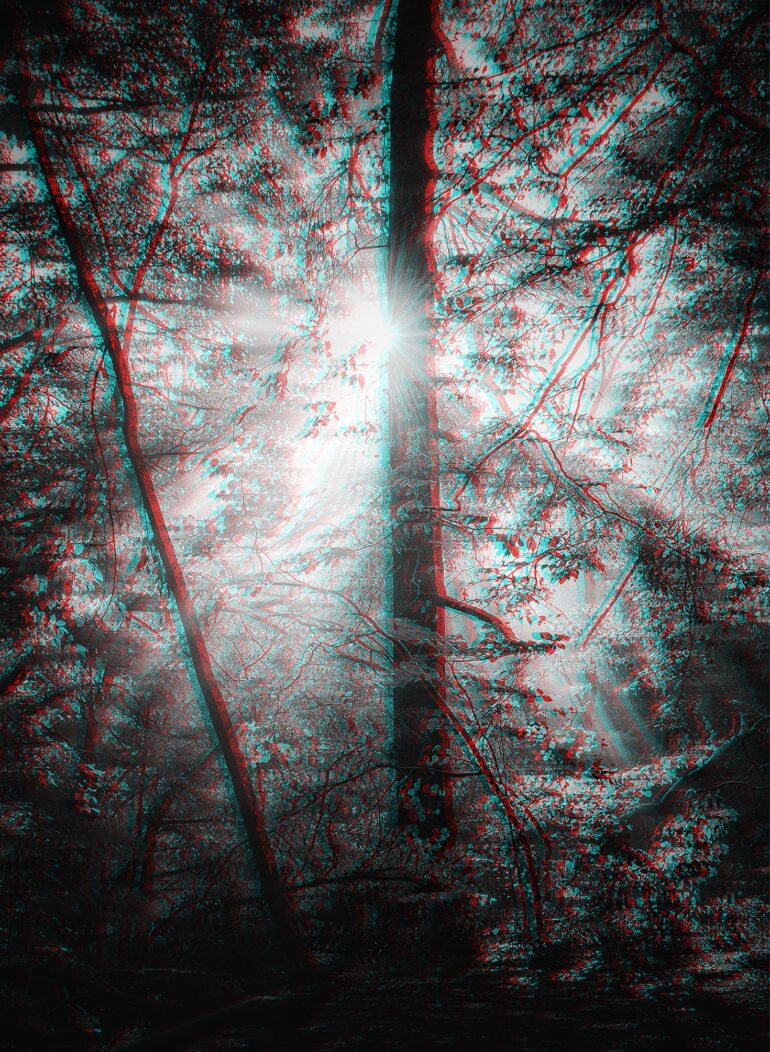

Global warming is driving certain animal species ever higher up the mountains. But once they reach the peak, there’s nowhere left to go.

She adds, ‘Biodiversity is another way that nature benefits humans.’ People’s interest in this area is growing. The Mountain Forest Project has noticed this too, as it depends on volunteers. More and more people are currently signing up because they want to do something for the environment, Dunja L. Meyer confirms. Coronavirus seems to have reinforced this trend. A lot of people are staying in Switzerland. And the project provides these volunteers with a week of discovery and learning in the mountain forest environment. For schools in particular, such project weeks often offer key experiences that cannot be replicated in the classroom. ‘Stand on the slopes of a steep mountain forest, looking down at the village below, protected by the trees, and you understand straight away that life in Switzerland would be impossible without protection forests,’ she states. However, the foundation does not survive on voluntary work alone. To facilitate these activities, the foundation relies on donations. A project week is, after all, associated with high costs: professional supervision, board and lodging, transport and equipment. They are therefore as dependent on large and small donors as they are on voluntary workers.

There is no such thing as ‘too many’ or ‘too few’

The mountain environment is also home to the Swiss National Park. Here, the focus is on the conservation area as a whole. ‘We not only protect animals, plants and habitats but all of the natural processes, too – the ecosystem as a whole,’ points out Hans Lozza, head of communications at the National Park. Following an avalanche, certain species may disappear while others will find a new habitat. ‘We don’t make value judgements. There is no such thing as ‘too many’ or ‘too few’ of a species. The number of each simply reflects the current balance of power.’ This is the approach the park has taken ever since its founding in 1914. ‘It was a time of economic development and a boom in tourism. Many resources such as forests or wild animals were overexploited and large parts of the mountains were used as pasture,’ the head of communications states of the park’s early years.

Intensive mining, deforestation, lime burning and grazing transformed the area around Zernez. In Basel, a group of urban, middle-class individuals – predominantly natural scientists – recognised the need to act. They wanted to set aside a piece of nature ‘for all time’, preventing any human use and allowing it to develop naturally. Some of the issues have changed since those days. ‘But the pressure on natural resources is still high,’ states Hans Lozza. ‘New threats have arisen. For example, excessive tourist use of the Alpine region. There is very little refuge for the animals – in summer or winter.’ The change in the landscape and the consequences for wildlife are also being monitored by the Swiss Ornithological Institute in Sempach. In Switzerland, people automatically associate Sempach with birds, but not because this is an exceptional region for ornithologists.

‘It’s to do with the organisation’s history,’ explains Livio Rey. The founder, Alfred Schifferle, lived in Sempach. The Swiss Ornithological Institute was set up in 1924 to research bird migration in the Alpine region. Thirty years later, it was turned into a foundation. Its work remains highly relevant. Biologist and media spokesperson Livio Rey explains, ‘Species that used to be common have practically disappeared as a result of more intensive farming.’

A major crisis

On the other hand, Livio Rey points out that ‘new’ species have appeared in residential areas. Many garden species we see today are forest dwellers that have ‘immigrated’. He names the blackbird, the chaffinch and the great tit as examples here. The vegetation found in an area such as a park is sufficient for species such as these. However, he is keen not to see this development in too positive a light. ‘Residential areas may have expanded, but the number of birds has not increased at the same rate,’ he points out. Over-manicured gardens that are mowed too frequently or consist mainly of gravel are of no value at all to wildlife. And the owners often plant species that are not native to the region. Livio Rey sums up, ‘Residential areas are expanding, but garden birds are not benefiting.’

The expansion of residential settlements has inevitably made them a focus of discussions on sustainability and the environment. The Sophie and Karl Binding foundation redefined its environmental funding activities to focus on biodiversity in residential areas. ‘In 2018, the foundation board decided to launch a major new project focusing on biodiversity,’ explains Jan Schudel, regional head of environment and social issues. And he recognises an urgency here: one third of the plant and animal species in Switzerland are under threat. Dry meadows and pastures have been particularly affected. According to the Federal Office for the Environment, they have decreased in area by up to 95 per cent since 1900. ‘A creeping loss,’ comments Jan Schudel.

‘It rarely makes headlines, despite the fact that this is a major crisis.’ By focusing on biodiversity in residential areas, the foundation aims to tackle the issue and raise awareness. ‘It’s about the diversity of nature on our doorsteps, and also of the policymakers,’ states Jan Schudel. ‘Those are the people we want to reach. Our goal is to call attention to the biodiversity that exists in built-up areas.’

Two gigabytes of data

The Binding foundation has created an award with the aim of increasing awareness of the issue. The first ever Binding Prize for Biodiversity, worth CHF 100,000 to the winner, will be awarded by the foundation in 2021 (after this publication went to press). Interested contenders had until 31 January to submit their projects. Even the call for entries had a huge impact. ‘We were sent a total of two gigabytes of data,’ states Jan Schudel. ‘You can see huge commitment in these projects. School classes took part, whole administration departments worked together. We received some powerful videos – it’s wonderful when you get to experience something like that.’ Plant-for-the-Planet also wants to get people involved. ‘One trillion trees is equivalent to 150 trees per person on the planet,’ calculates Marianne Jung. ‘Yes, that seems a lot at first. It’s a Herculean task.’ However, if businesses decide to join in and, for example, plant their own forest so they can go carbon neutral, that is a lot of trees. Plant-for-the-Planet is not looking to plant all of these trees themselves. Pirmin Jung explains, ‘Alongside our own planting activities, we want to coordinate all of the other tree planting projects in various countries and regions and provide interested private and institutional donors with easy access to these projects via the Plant-for-the-Planet app.’ The two founders’ commitment to planting trees is linked to their professional background. As civil engineers, they rely on wood as a raw material. ‘There is a hidden bonus there. Each tree is planted and at some point it becomes old. If we didn’t harvest it, it would fall and rot of its own accord over the course of time – and the CO2 stored in the wood would be released into the atmosphere again,’ he explains. ‘It’s clear to us that, on the one hand, we need to conserve the rainforests and jungles. Without compromise. But the rest of the forests should be actively and, above all, sustainably managed to absorb as much CO2 as possible and, in the long term, lock it in products and buildings.’ They believe in mixed forests, tailored to the local situation. Individual trunks should be harvested from these from time to time and young trees planted in their place.

Birds are popular with the public

For Livio Rey too, the foundation’s work was a vocational calling. ‘I always wanted my work to centre on nature, raising awareness and improving understanding.’ As an example, he explains that he feels it is important to show people that crows, for instance, are highly intelligent and social creatures. He is keen to share his appreciation of these animals. It helps that birds are popular with the public. People feel a connection with them. During the first lockdown, the Ornithological Institute received an extraordinary number of enquiries. ‘People noticed the birds more. They wanted to identify the birds they had seen and asked us how to put up nest boxes or make their gardens wildlife-friendly.’ He appreciates there is an emotional connection there. But when it comes to environmental matters, it is hard facts that count. And these are less positive. ‘Rare species are becoming even rarer,’ Livio Rey points out. Developments in the wetlands and agricultural areas in particular are exacerbating the situation. Many endangered species live in these habitats. And, of course, climate change is a major concern. ‘Habitats could become very confined for birds that live in the mountains. But Switzerland has a huge responsibility towards mountain birds,’ states Livio Rey. If the temperature rises, birds that live in cooler temperatures will be forced to move to higher ground. ‘But at some point, they’re going to run out of mountain,’ he states. There are some success stories to report, however. Where major efforts have been made, improvements have been observed. Livio Rey cites the example of the lapwing. ‘It was in danger of extinction, but today things are looking better, thanks to conservation efforts.’ Many species, however, are not so easy to encourage, but the fact that people are recognising the importance of sustainability, nature and the environment helps. ‘Birds are not unconnected to the climate issue. They are just as affected by climate change as humans are,’ he explains.

Today, forest dieback is called climate change

Climate change is also impacting on the mountain forest. ‘Today, forest dieback is called climate change,’ states Dunja L. Meyer. It is causing the mountain forest serious problems. When it comes to tolerating dry spells and heat, not all trees are equal. The major challenge is to make the mountain forest, and the protection forests in particular, fit for a future that is unpredictable. Researchers are looking for trees that can tolerate aridity and heat well. According to the latest findings, ‘The spruce, which was commonly used for reforestation purposes in the past, is unfortunately not very resistant to aridity, as it has shallow roots.’ It helps that more and more people are responding to the issue. An ever increasing number of organisations are focusing on the environment. This is positive. Work is also steadily increasing, she points out, and, rather than viewing other organisations as rivals, she sees them as fellow campaigners for a common cause. Marianne Jung has a similar point of view. ‘All activities that help prevent the planet from heating up by more than two degrees are positive. We don’t see anyone as rivals – we’re all in it together. The activities of the climate movement are raising awareness and that is helping us directly.’ Through their work, Plant-for-the-Planet also aims to reach young children and teenagers on the subject of climate change. Up until now, the international movement has trained 90,000 teenagers and children in 75 countries as ambassadors for climate justice. They learn what climate crisis and climate justice are, how planting trees can improve biodiversity, soil fertility and the local climate, and what proactive steps they can take themselves.

Not just the rainforest

In order to be as effective as possible in their new, environmental role, the Sophie and Karl Binding foundation consulted with expert practitioners in the field, with organisations such as the Swiss Biodiversity Forum and Pro Natura. This enabled the foundation to develop a funding area focusing on biodiversity and the improvement of high-quality landscapes. In implementing projects, consideration of the other two funding areas (social and cultural issues) also plays a role. ‘We make every effort to ensure that there are no internal inconsistencies,’ states Jan Schudel, citing as an example the occasion when concern for the climate meant that a dry stone wall repair had to be carried out without deploying a helicopter. They work with other foundations and organisations on many of their projects. It can be difficult to be a game changer on your own. Resources need to be used sensibly. And need to make an impact. Including with the general public. This is where it is hoped the new prize will play a key role. The Forest Prize, which the foundation awarded for 30 years until 2016, succeeded here. The aim now is to do the same for biodiversity, because attention is urgently needed. ‘For some species on the red list that are at risk of extinction, the trends are dramatic,’ states Jan Schudel, adding, ‘but we have seen a significant downturn in more common species too.’ Swiss society is not fully aware of the local problems that exist. Communication is therefore vital. There is a gulf between scientific findings and public perception. ‘It’s not just the rainforest that is under threat,’ he explains. ‘We have species here, too, that are close to extinction or endangered.’

An exceptionally long-term project

In outlining its main responsibilities, the National Park recognises the importance of communication. Publicity is one of these responsibilities, alongside conservation and research. The head of communications points out, ‘All three responsibilities are important. Conservation provides the framework for this long-term experiment. Research reveals how nature develops over long periods of time without human intervention. And the publicity work enables people to access wild nature and encourages support for this exceptionally long-term project.’ Clear safeguards are in place, and these enable tourism. People have to follow set pathways, no camping is allowed and access is on foot only. ‘We enforce these protective measures, with fines if necessary,’ states Hans Lozza. Making visitors stick to the paths ensures that there is far less disruption for plants and animals than in areas where people are free to roam at will. Parks offer an opportunity to open people’s eyes. ‘We can turn them into fans of unspoilt nature,’ states Hans Lozza. Good publicity is important to the park, as it is becoming more difficult to find major donors for unspectacular ‘background’ work. One challenge currently in the offing is further development of the UNESCO Biosfera Engiadina Val Müstair. The Swiss National Park acts as a core zone of this biosphere reserve. Hans Lozza: ‘The aim is to create a model region, where people take a sustainable approach to natural resources.’