Foundations linked to businesses and corporate foundations that are active in the environmental sector are using their networks and know-how to make a difference.

‘Environmental issues are becoming increasingly relevant. And it is becoming more and more important for us to find new solutions,’ says Vincent Eckert, director of the Swiss Climate Foundation. ‘If we want to achieve our climate targets, we need innovative technologies,’ he asserts.

The Swiss Climate Foundation is a voluntary initiative by businesses, and is currently supported by 23 partner companies: service providers, banks and insurance companies in Switzerland and Liechtenstein who are donating the funds they receive from the redistribution of the CO2 levy to the foundation. A CO2 levy is charged on fossil fuels in Switzerland, and a portion of the funds collected is redistributed to the companies depending on their payroll. In 2020, this amounted to 188 million francs. Through this system, companies that use less oil and gas get back more than they originally paid.

The partner companies donate this money to the Swiss Climate Foundation. Every year, the foundation invests between three and six million francs in environmental projects run by SMEs. ‘By pooling the resources of our partner companies, we are ensuring that the redistribution of the CO2 levy has the maximum possible impact. The Swiss Climate Foundation can use these funds to make a difference,’ says Eckert.

Good for the economy and the environment

The Swiss Climate Foundation uses the money to support projects by SMEs, for example those implementing measures to increase energy efficiency. It also assists companies that are developing innovative products and technologies that contribute to environmental protection. ‘Developing innovative solutions in particular can take a long time,’ observes Eckert. ‘Many SMEs are reliant on external support for this process. This is where the Swiss Climate Foundation and its straightforward funding come in.’ Since the foundation began, around 1,700 SMEs have benefited from its support. And the partner companies benefit, too: they gain access to a wide and dedicated network, innovations, a strong voice and a reputational boost. ‘The foundation’s motto is: “By business, for business and the environment.” And this is a principle that has borne fruit,’ says Eckert.

A complementary role

Companies contribute a considerable amount to sustainability causes through foundations – a commitment that often goes unrecognised by the public. Many businesses engage directly through their own corporate foundations, which benefit from their proximity to the company. This strategy also has advantages for the companies themselves.

‘The foundation has a complementary role,’ says David Nash, Senior Manager of the Z Zurich Foundation, which was founded in 1973 as the Zürich Vita Alpina Jubiläumsstiftung and renamed in 2008. Over the last few years, Zurich Insurance has developed its own sustainability strategy to take advantage of this interplay, explains Nash. The insurer focuses on counteracting global warming as per the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement: reducing its own CO2 footprint and encouraging its customers to act in more environmentally friendly ways. The foundation, by contrast, directs its activities towards supporting vulnerable people affected by climate change.

Global warming leads to extreme weather patterns, heavy rain and storms. These affect individuals. ‘We go where the people are and do our work there,’ says Nash. ‘We want to make affected communities aware of these changes and help them understand the need to adapt.’ After all, natural hazard related disasters will only become more prevalent in future, he says. The foundation’s Flood Resilience Alliance programme aims to help by assisting people in making their local communities more resilient to future floods.

A more resilient world

As part of its efforts to create a more resilient society, the Swiss Re Foundation has been active in the area of sustainability since 2011.

To illustrate the kind of work the foundation does, director Stefan Huber Fux gives the example of Yucatán on the Mexican peninsula: ‘You’ve got paradisiacal Caribbean beaches, and off the coast you have one of the world’s most significant reefs, which boasts an incredible amount of biodiversity.’ The reef is also of central importance to the local population, both for the fishing industry and for the region’s billion-dollar tourism industry. But Yucatán is increasingly being hit by hurricanes in particular, often with a disastrous impact. ‘Research has shown that an intact reef is the cheapest and most effective form of protection for the coastal region,’ says Huber Fux. Based on this knowledge, the Swiss Re Foundation has collaborated with local partner organisations to put a monetary value on the reef for the first time. This, in turn, has paved the way for a form of insurance cover in which beneficiaries of the reef’s protection – such as hotel owners – cover the costs. ‘Our focus is on understanding how a reef can sustain its function for the local area in the long term, and how local groups can do the necessary “maintenance work” themselves,’ Huber Fux explains.

At a coral breeding centre, young corals are grown so that they can later be planted in badly damaged parts of the reef – similar to a tree nursery. Huber Fux is convinced that it is precisely this kind of cross-sectoral work that will enable us to tackle the huge challenges we face on our journey towards a more resilient, robust world. The company’s own network is key to achieving this. ‘Especially given that we are a corporate foundation, we see our employees as important partners whose expertise can play a major role in developing new solutions,’ he asserts. The foundation also benefits from the company’s reputation. ‘We are a relatively small charity in global terms, so Swiss Re’s reputation definitely opens doors for us,’ says the foundation’s director. One of the key pillars of their successful cooperation, according to Huber Fux, is the fact that Swiss Re as the parent company shares the same vision of creating a more resilient world. There are limits to the collaboration, however.

The foundation is active in many countries that are not top priorities for Swiss Re. The focus on local impact and a considerable degree of independence from its parent company are also central to the work of the Syngenta Foundation. For 40 years, the foundation has been dedicated to promoting sustainable smallholder agriculture in developing countries. ‘We are able to address issues that matter to smallholders locally, but which aren’t of much commercial interest on a global scale,’ says Paul Castle, Head of Communications at the Syngenta Foundation. While the company Syngenta aims to make a profit, its foundation can operate free of short-term financial pressure or any worries about turnover and margins.

Castle nevertheless sees economic viability as part of the foundation’s work: ‘In addition to environmental and social sustainability, economic sustainability is also a factor,’ he says. Agriculture can only be truly sustainable if it is an attractive career option for future generations. ‘It’s far more sustainable for smallholders if development focuses on putting market systems in place rather than giving hand-outs,’ continues Castle. ‘But sadly, many people still don’t see it that way.’

Constructive collaboration

SENS is dedicated to an area that is of simultaneous commercial, environmental and economic interest. Since 1990, SENS has been demonstrating how a foundation can make a real difference. Its donors include Coop, Migros, RUAG and the canton of Aargau. The foundation addresses companies’ need for commercial, environmentally friendly waste disposal – at an overarching level and independent of the competing companies, which act in accordance with the extended producer responsibility (EPR) policy. It guarantees a take-back system for electrical and electronic household appliances through the advance recycling fee (ARF). Communication with its partners is correspondingly important.

‘Our cooperation with commercial companies has always been, and remains, close and collaborative,’ says Sabrina Bjöörn, Head of Marketing and Communications. She is responsible for ensuring sustainable development. Partners can address their requirements directly, and the foundation takes them into account. It’s an extremely constructive form of collaboration, says Bjöörn: ‘Especially because sustainability and resource conservation is at the forefront of what we do. Competition doesn’t play a role in these partnerships.’

The voluntary nature of the system is also a decisive factor, and has enabled it to be incredibly successful – as the figures show. Over the past 30 years, SENS has ensured the correct disposal of 1.2 million tonnes worth of electronic devices. Online retail poses a challenge for the future, however. ‘Thus far, online retail in Switzerland has complied well with the ARF,’ says Bjöörn. But the situation is more difficult when it comes to foreign online retailers. In addition to giving consumers the option of paying the ARF themselves, therefore, SENS also works with foreign organisations. Collaboration with key partners within Switzerland is also crucial to success. The most direct way to achieve this is having a representative on the board of trustees. ‘The Association for Household and Commercial Electronic Devices (FEA), for example, is on our board of trustees, where it is able to represent the needs of its members,’ says Bjöörn.

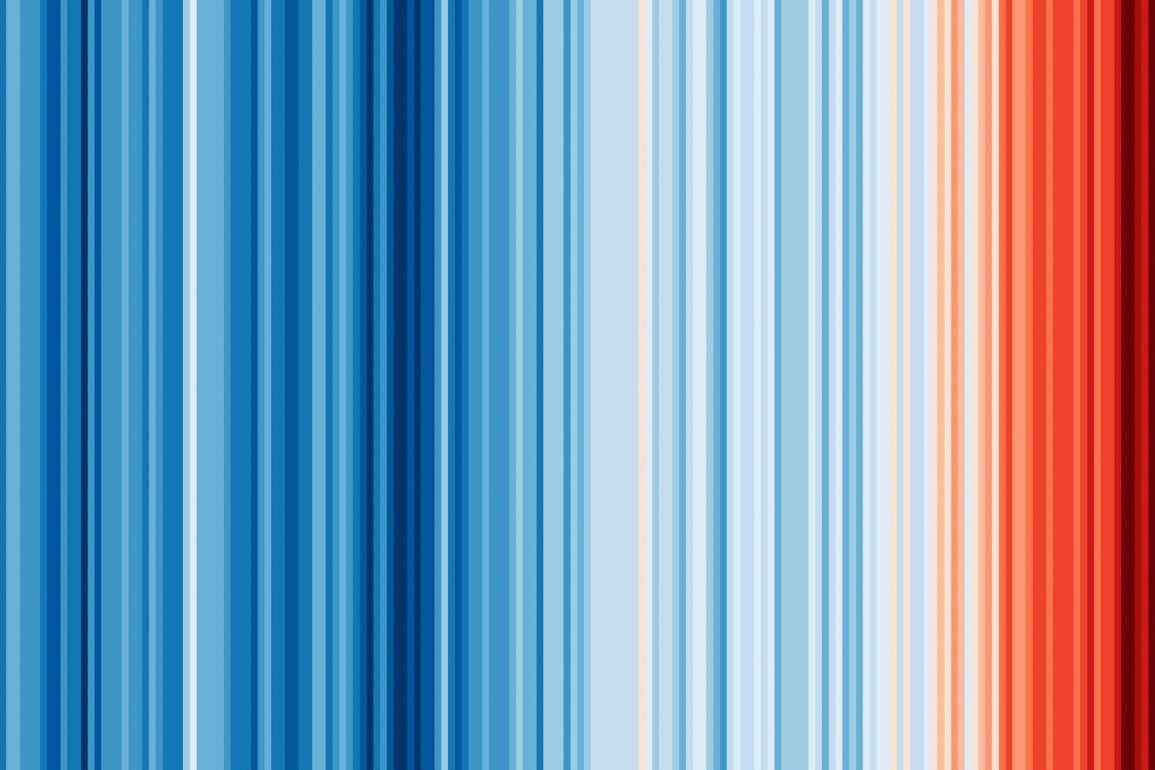

European warming stripes 1901–2019.

The colours show deviation from the average temperature, cooler in blue and warmer in red.

A strong board of trustees

For many foundations, having company members on the board of trustees is a way of strengthening ties with the industry. This has a twofold effect: it provides access to expertise and important contacts from the company, while also establishing the role of the foundation within the company. ‘This approach has been very helpful for us,’ says Stefan Huber Fux. In future, however, once the foundation is established, he intends to involve more external experts. The situation in the Z Zurich Foundation is similar. The current board of trustees is drawn almost entirely from the company itself. ‘This means that the foundation is very close to the business,’ says Nash, which helps with ongoing support and streamlines collaboration. ‘Aligning with the company also helps us to stay relevant,’ he adds. It demonstrates that the foundation is in the strategic interests of the company. However, one disadvantage is the lack of an external perspective from which to strengthen decisions. Paul Castle presents a similar picture. The fact that Erik Fyrwald, CEO of Syngenta, chairs the foundation’s Board is a reflection of the close ties with the company. ‘There are many advantages to having top-level links. Erik’s three predecessors were all Chairmen of the Syngenta Supervisory Board,’ says Castle. He nevertheless expresses a common view at corporate foundations: ‘We’re glad that there are no other company employees on our Board. That gives us a good balance between proximity and independence.’ Castle emphasizes that the foundation is a separate legal entity. Its segregation from the business is laid down in its statutes, which allow the foundation to operate only outside Syngenta’s commercial activities.

At the same time, the Syngenta Foundation is one of quite a few corporate foundations that work in similar thematic areas to their founding companies. This similarity in their fields of activity has the major advantage of enabling expertise to be shared. ‘We could talk together for hours about healthy soil, sick plants and digital tools,’ says Castle. However, the foundation’s independence allows it to address a much wider range of topics. Irrigation equipment, smallholders’ organisations and their market access, for example, are not high on the company’s agenda. Research and Development partners with which the foundation works are usually interested in crops of no commercial significance to a multinational. These include cassava or the Ethiopian staple grain, teff. The Syngenta Foundation always works with partners. ‘These include other foundations – often as funding partners – and a wide range of further organisations, from NGOs to government ministries, universities and insurance companies,’ says Castle.

Swiss warming stripes 1864–2019.

It may look like modern art, but the increase in red stripes strikingly visualises rising temperatures.

Cooperation is key

Working together is becoming more and more important. Even in the face of the pandemic, the topics of sustainability and the climate crisis are gaining in significance. A climate-neutral future requires new innovations – solutions for creating carbon-neutral real estate portfolios, or removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it long-term, for example. In order to effectively promote these technologies in the long term, everyone needs to get involved.

Companies have to address the issue – and they want to. ‘We’re very pleased about that,’ says Vincent Eckert. ‘We are seeing the interest in environmental issues increase.’ The Swiss Climate Foundation’s expertise is in demand. Companies have come to realise that they cannot tackle environmental challenges alone, states Eckert: ‘They need to form alliances.’ Stefan Huber Fux also highlights the need for joint efforts. He is pleased to see the increasing awareness among young people and their willingness to play an active role in shaping their future. ‘They’ve recognised that the climate crisis is a reality that they are going to have to live with much longer than many of the people who are currently calling the shots,’ observes Huber Fux. Time is running out. People will be slow to realise that 2030, the next milestone for climate policy, is rapidly approaching, thinks Nash.

‘It’s now happening within our lifetime.’ This makes the urgency clear. However, he considers patience to be the greatest challenge. ‘Despite the urgency to take action, we need to convince people that the effects won’t necessarily be immediate.’ Overcoming this existential crisis is the work of years, not of days, and it demands new forms of partnership, like those of the Flood Resilience Alliance, which uses the collective intelligence of all its participants. This requires everyone’s abilities and resources, says Nash, explaining that the intellectual capital or ‘toolkit’ produced by this work should be open to everyone. ‘We are taking a collaborative approach. The foundation is one part of that,’ he says. ‘We need to take into account all the available perspectives – no single sector can solve the problem alone. The more partners we have from different sectors, the greater the impact will be.’