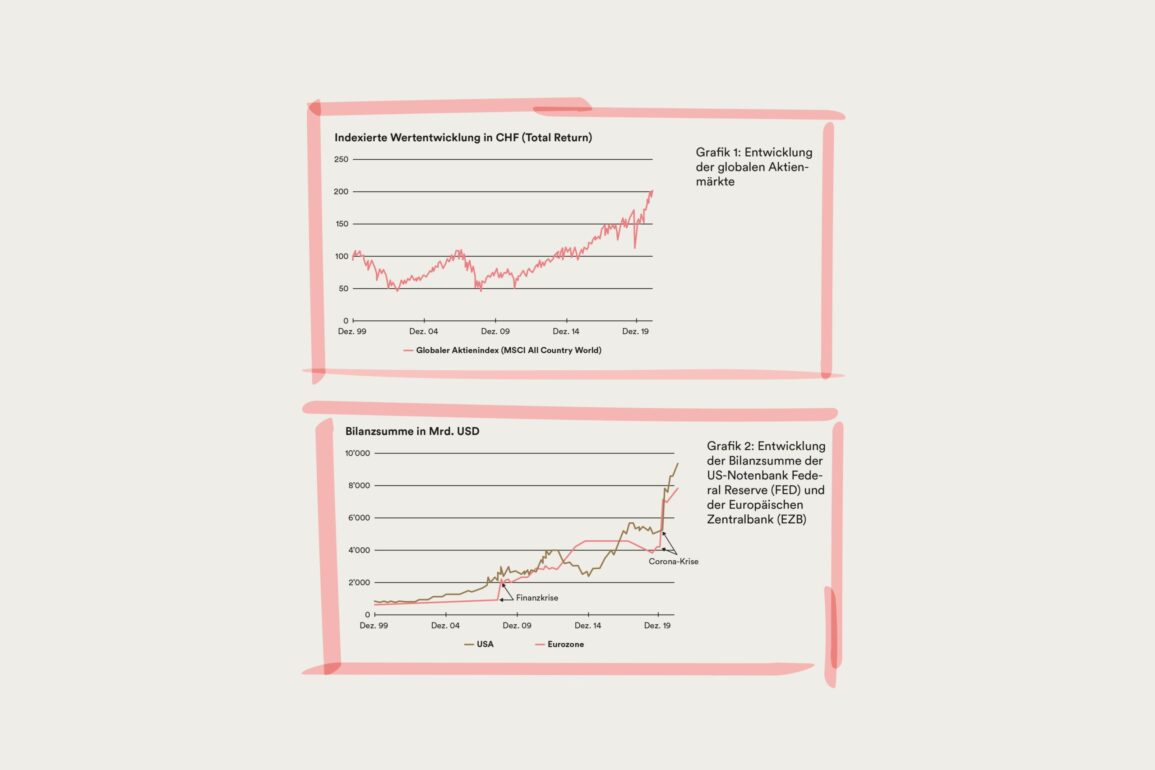

The global stock markets are jumping from one all-time high to another. They have more than quadrupled since the crash in 2007/8, corresponding to an annual return of more than 13%, and they have even escaped the coronavirus crisis almost unscathed.

Share prices are now up a good 20% on their levels before the crisis. Measured from the lowest point, prices have increased by more than 82%, almost doubling within 15 months (see Fig. 1).

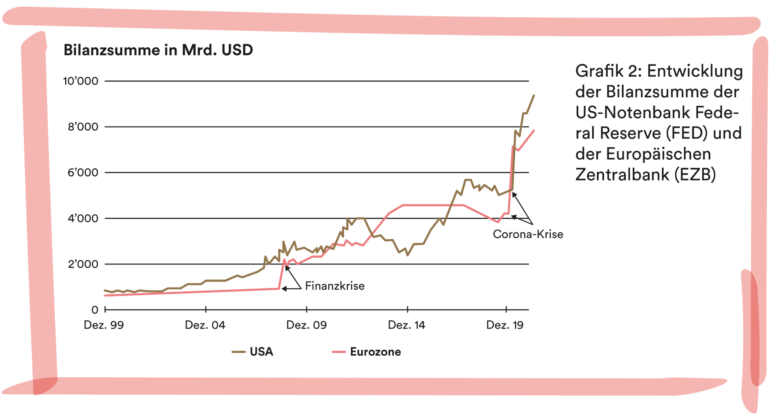

The courageous intervention of the central banks is one of the major drivers of this trend: in the wake of the financial crisis, they reduced their base rates (sometimes even into negative territory), providing the markets with enough liquidity through to the present day. Over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, many central banks even increased their exposure, leading to a doubling of their total assets in the US and Europe (see Fig. 2).

In principle, this approach can be continued indefinitely, with no time limit. If the additional liquidity remains in the financial markets, this will lead to inflation (continuous price increases) on the stock markets, albeit not in the real economy. Share prices will head northwards, while the economy undergoes minimal growth or even experiences a crisis. The financial markets are decoupling from the real economy, as it were – creating a bubble. What remains are higher share prices and increased central bank total assets.1

The expansionary monetary policy is expected to continue and the low interest rate environment to hold firm. Stronger in times of corrections and crises, and less intense in periods of economic boom. Share prices should thus continue to receive a tailwind. However, in contrast to the past, we expect crises and correction phases to occur more quickly and with more ferocity, something we have already seen during the coronavirus crisis. Within a short space of time (23 days), the global stock markets lost more than 35% of their value. Such a rapid price loss is unique in the history of the financial markets. This can be explained partly by the swift increase in systematic trading strategies2, which act on the financial markets autonomously free of emotion – and at lighting speed.

What could bring an end to climbing prices?

An exogenous shock, such as another wave of the pandemic, would affect the financial markets only in the short term. Like the previous waves, this wave would also be flattened by injecting more liquidity.

In a sustained crisis on the stock market, a trigger is needed that reins purchases in and/or pushes investors to sell their securities en masse. This could take the form of a political decision that restricts the central banks’ purchasing programmes, or even brings them to an end. But as these banks are independent (or at least, they should be), this scenario seems unlikely. Conversely, if investors were to panic-sell their securities, inflation would pass from the financial markets to the real economy. Central banks would be forced to increase their base rates to stem the tide. Credit would become more expensive and the economy would suffer. At the same time, share prices, already drifting lower, would fall, leading to a financial and economic crisis.

These scenarios are extremes and it’s true that they rarely appear suddenly and with great force. That said, we think small-scale movements in either direction are more probable. In order to protect a portfolio from as many rough patches as possible, it is important to have a wide range of assets. Invest in different stocks, sectors, regions and currencies. Add real estate stocks and/or funds and gold to your portfolio and avoid long-term bonds when interest rates are historically low.3 Maintain liquidity reserves that are sufficient to cover current and future expenditure.

Would you like to know more about the individual and optimal allocation of your foundation’s assets?

Talk to your bank.

1 In addition, governments also launched economic stimulus packages to an unprecedented extent during the coronavirus crisis. This invigorated the real economy and has led to increased national debt.

2 These are computer programmes that automatically trade securities on the exchanges according to certain patterns.

3 If inflation and interest rates increase, bond prices will decrease. This asset class thus has a potentially high risk of loss for investors.