Education and knowledge are the basis for active participation in our society. Money and awards, network and coaching are how foundations support top-class research and basic training, both for people in Switzerland and around the world.

‘We need money for research, but on its own it’s not enough,’ says Rudolf Aebersold, professor at ETH and the University of Zurich. ‘Successful research hinges on people; that is, researchers and students,’ adds the systems biologist. Last year, the Marcel Benoist Foundation awarded him the eponymous Swiss Science Prize, which it has presented since 1920.

When the foundation evaluates a research performance, the social benefit is always in the foreground. The prize is now firmly established and has been dubbed the ‘Swiss Nobel Prize’. Rightly so: ‘Eleven winners of the Marcel Benoist Prize have also received a Nobel prize, most recently the astronomer Professor Michel Mayor in 2019,’ says Aurélia Robert-Tissot, the foundation’s secretary.

Effective tools

The foundation was established in 1920. Marcel Benoist, born into an upper-class family in Paris, succumbed to smallpox in 1918. He had no children and dedicated his time to a wide array of interests. From 1914, he spent most of his time in Lausanne and left the bulk of his assets to the Swiss Confederation, which in return undertook to present a science prize every year. Since the foundation repositioned itself in 2018, a committee of international experts has selected a candidate from the nominations received. However, the Board of Trustees is responsible for making the final decision. The Board includes representatives of Swiss universities and the French embassy, with Federal President Guy Parmelin, head of the Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research, as its president. Alongside the prize money of CHF 250,000, the award means increased visibility for winners. Robert-Tissot says: ‘It can open doors, enabling people to make important contacts in the fields of research, business and society.’ And Aebersold adds: ‘In any case, prizes and awards are an effective tool to make scientific progress and its social significance accessible to a wider audience. This communication is of fundamental importance; after all, it’s ultimately the general public, i.e. taxpayers, who pay for research.’

Core financing in place

In Switzerland, research is facilitated primarily through state funding. In its study ‘Philanthropie für die Wissenschaft’, the Center for Philanthropy Studies (CEPS) at the University of Basel discovered in 2014 that 70% of the University of Basel’s funding came from state sources. Conversely, John Hopkins University in the US and Oxford University in the UK receive no state funding whatsoever. The director of CEPS and co-author of the study, Professor Georg von Schnurbein, believes that this relationship fundamentally is no different today.

‘In Europe, and continental Europe above all, universities are funded primarily by the state. In the US, conversely, top private universities are funded by financial donations.’ As a result, he explains, the relationship with donors is different: in the US, there is an expectation placed on wealthy citizens, in particular alumni. ‘If you have money, you have to commit financially to research,’ says von Schnurbein. It’s different in Switzerland, where core funding is available. General research is safe, meaning that donors can put forward their own ideas to a greater extent. ‘And, in turn, universities can collect donations in a targeted manner, so they can pursue their strategic objectives better,’ says von Schnurbein. This has an impact on individual researchers, who gain access to various funding options. Since researchers in Switzerland are offered various funding agencies, such as the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF, along with foundations and donations, Aebersold sees them as being in a privileged position. Funding bodies such as the SNSF provide funds in a transparent, fair way, he says. Conversely, foundations are much more focused on a particular geographical area or topic, but in exchange are more flexible in their allocation. ‘In an ideal world, public and private funds complement each other,’ he says, ‘and that works really well in Switzerland.’ This interplay is key to creating an appealing research environment and this applies not only to funding. ‘In the life sciences, research is increasingly turning to technology and data processing methods that often cannot be covered by an individual research group or institution,’ says Aebersold. ‘Foundations can play a role in making research hubs more attractive by proactively contributing to networking and training for researchers or development of the infrastructure.’

Photo: Paul Berclaz, Giorgio von Arb, zVg

Photo: Cyril Cordoba, zVg

Expert network

Networking and supporting researchers are two of the qualities that make the work by Stiftung Synapsis – Alzheimer Forschung Schweiz AFS stand out, alongside the organisation’s financial involvement. The foundation supports research into Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases at universities in Switzerland. To this end, a public call for submission of research projects is launched every year.

Since 2018, the foundation has also invited the researchers it funds to a scientific event, as Heide Marie Hess explains. She is responsible for communication and promotion of research at Synapsis and says: ‘We want to foster networking and the exchange of knowledge. Time and again, the event gives rise to new ideas for collaboration between researchers.’ Members of the scientific advisory board also participate in the event.

This body consists of international experts who are responsible for selection of the research projects. Its members have broad-based expertise, enabling submissions to be assessed objectively and on a sound basis. The advisory board can also offer support before the award decision is made. ‘It might be the case that a member of the advisory board thinks a particular project idea is very innovative, but that the application has certain formal defects,’ says Hess. In this case, the researcher will receive detailed feedback that they can use to make a new application, or they might be given the opportunity to submit information retrospectively. Helpful contacts are also passed on. Its comprehensive funding work and elite advisory board mean that the foundation has established itself as the most important funder of research in the field of neurodegenerative diseases in Switzerland. ‘The professors know our name,’ says Hess. The 50 project applications submitted to the foundation in 2021 are testament to that.

Clear reporting

‘Synapsis’ reputation and the work of the scientific advisory board are also important for donors,’ says Barbara Rüttimann, responsible for institutional fundraising and major donors. Regular reporting and the opportunity to meet researchers help Synapsis to be transparent about what happens with the money. This is crucial, in particular when working with other grant-making foundations. If money is left over at the end of a project, the foundation asks for it back so it can ensure that the funds are used as the donors intended.

Rüttimann says: ‘We work closely with researchers, and that shapes our work. It allows us to be successful.’ The end of a project is also followed by a self-regulation. ‘After a project has finished, established researchers are not allowed to submit a new application for a year,’ says Hess. This prevents the same research groups from receiving support time and again: ‘We would run the risk of always supporting the same research approach, and not giving other groups a chance,’ she says. It makes sense to prevent this, since nobody knows what ultimately triggers Alzheimer’s. New research approaches could advance the decoding of the mechanisms of origin. in addition, the foundation offers targeted support for up-and-coming researchers. ‘Postdocs aiming for a group leader position or assistant professorship often find it tricky to get funding during this transitional phase. We want to bridge this gap,’ says Hess. ‘The aim is to get young, talented researchers interested in researching neurodegenerative diseases.’

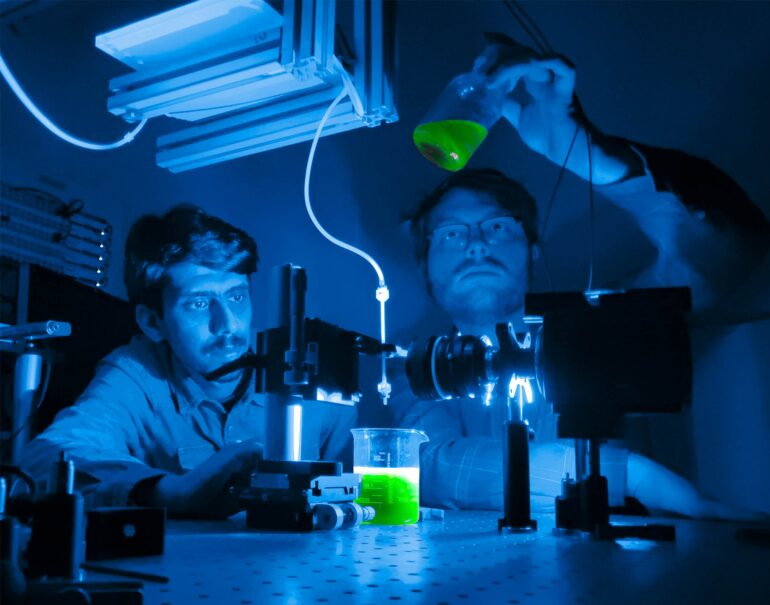

They include Arseny Sokolov. A neurologist, he received a Career Development Award from Synapsis in 2020, which was intended to help him in his development towards a professorship. He reached this goal at the start of July this year, with a position at the University of Lausanne. His study began at the same time. ‘Our research project looks at the value of serious video games for assessing cognitive deficiencies in people with dementia,’ he says.

It focuses on assessment and rehabilitation in the early stages of dementia, and involves clinics in Nice, Bern, Lausanne and San Francisco. ‘There is still little data on these technology-based methods,’ he says. It is wonderful that their project can fill this niche. He’s also impressed by the foundation’s approach to supporting research. ‘We worked closely together from the start and I received outstanding advice from the advisory board,’ he says. And his research is generating results. Dementia research is a major issue in society: funds are available for drug research, but research into rehabilitation is in its infancy. ‘Synapsis recognised the relevance and potential of this field of research, which the WHO is actively exploring with a group of experts in which we are participating.’

Unconventionally flexible

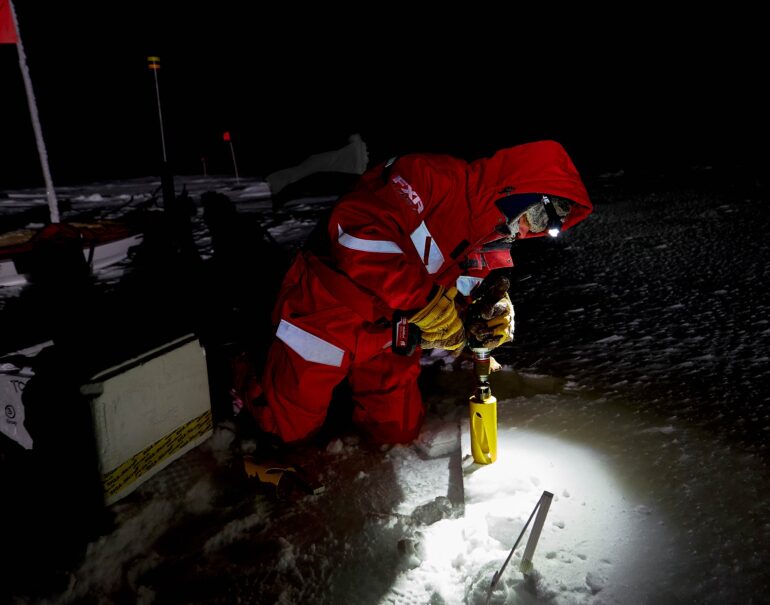

When Sokolov was a student, it became clear to him that he was interested in how the brain regenerates after an injury. His passion for this field of research grew when he was in California, where he was impressed by the close interaction between research and industry in San Francisco. He was also impressed by the philanthropy there, but the quality of Switzerland as a research location won him over, leading to his move back to the country. ‘Switzerland should not shy away from international comparisons,’ he says. ‘This is shown by the research results.’ The involvement of philanthropy plays a part in this. ‘It’s indispensable when it comes to innovative, world-changing ideas,’ says Sokolov. ‘It enables researchers to pursue unconventional approaches and develop a dynamic that would take decades with traditional funding programmes.’ Synapsis is very aware of the fact that its funding serves to complement state funds. ‘Unfortunately, we do not have as much funding to give out as the Swiss National Science Foundation does,’ says Hess. ‘But in exchange we are more flexible to whom we award it. We can react to researchers’ needs quickly and on an individual basis, where it’s sensible and justified to do so, and try to provide support where we think there are funding gaps.’ The current coronavirus crisis demonstrates just how flexible and straightforward foundations can be in their work. The association SwissFoundations launched the education fund ‘Foundation for Future’, in conjunction with diverse grant-making foundations, because the state had not developed a uniform solution to support students.

‘Many students ended up in financial distress because they had lost their part-time jobs, which they needed to stay afloat. They were at risk of going into debt and, in the worst-case scenario, dropping out of their studies,’ says Simon Merki, managing director of the foundation EDUCA SWISS. Schweizerische Stiftung für Bildungsförderung und ‑finanzierung manages the education fund, using the money to support students in need. In 2020, the year hard-hit by the crisis, the foundation received 1,688 applications, almost as many as in the previous four years combined.

‘Although the pandemic is now gradually flattening out and more part-time jobs are returning, the economic damage is far from over,’ says Merki. ‘With “Foundation for Future”, Swiss grant-making foundations are working together to do everything they can to maintain equal opportunities in the education sector.’

A clear strategy

Although foundations give out significant amounts of funding, it remains the state that has the greatest influence on the direction of research, putting paid to the idea that large donors threaten the independence of research. This was highlighted by UBS’ donation of CHF 100 million to the University of Zurich in 2012, which triggered outrage. Georg von Schnurbein sees this donation in a wholly positive light. ‘It made it possible to attract wonderful academics to Zurich, and Zurich is now one of the strongest locations in continental Europe for economic sciences,’ he says. It’s the students who benefit from this. ‘Today we need private, third-party funding to support cutting-edge research, but it is an addition to all the funding on offer.’ He’s well aware of these issues, as head of CEPS, which is itself funded by foundations. He points to the institute’s clear structure and another aspect that ensures research remains independent: the regulation of the research community.

‘If I want to publish my research, I submit it to an academic journal. Researchers who do not know the author’s identity subject it to peer review.’ This guarantees that academic output is independently assessed.

Photo: Nadine Arnold, zVg

Equal opportunities

The Jacobs Foundation supports research that looks at questions relating to education and also supports educational projects. This focus can be traced back to its founder, Klaus J. Jacobs, who believed that education was of fundamental importance for society.

‘He always believed that the next generation would bring forth change with renewed energy,’ says Alexandra Güntzer, the foundation’s Chief Communications Officer. He was convinced that education was the key to enabling children and young people to become creative, productive members of society. ‘He felt it was important that every child received a good education, no matter their social class or family background,’ says Güntzer.

The Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation promotes the project ‘2. Chance auf eine 1. Ausbildung’ (Second chance for an education). In fact, it does not fit with the foundation’s funding work, which supports culture and medical research in Switzerland and the UK. But, thanks to a donation, it can use the project to offer 50 adults in the canton of Bern the opportunity to step into the primary labour market by completing basic training.

‘These people often work in badly paid, low-threshold jobs,’ says the foundation’s managing director Guido Münzel. ‘And they are the jobs that are most at risk in a crisis.’ The project is conceived as a supplement to the support offered by the state. ‘We play only a secondary role,’ says Münzel. In other words, the foundation becomes involved only if there is no other way for the candidate to acquire funding.

However, it came to the realisation that candidates not only needed money, but also additional support, such as coaching or preparation for vocational school. So it shifted from simply funding the project to actually running it. ‘In fact, that’s not what we wanted,’ says Münzel. ‘But at the same time we wanted to offer the best possible support to people benefiting from our service.’ The foundation sought out collaboration with established institutions and cantonal authorities in order to work as effectively as possible. ‘It became clear that we were pursuing the same goal, integrating workers into the primary labour market.’ And this is where Münzel believes there are opportunities to be had due to the shortage of skilled labour; for example, in the healthcare sector. ‘We can see that there’s an opportunity here to integrate our programme’s candidates into the primary labour market.’ The foundation received 180 applications this year and chose 47 candidates. The budget for this runs to CHF 1.4 million and over the next few months the goal is to find all 47 an apprenticeship by August 2022. This is the third iteration of the project, but after this the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation will take a step back from funding it. Münzel believes that if the programme proves itself, a community of interests can be found to continue it.

Research and more

The Jacobs Foundation has also honed its focus with its new strategy. ‘We started as a research-supporting foundation,’ says Nora Marketos. Since 2009, the foundation has used the Klaus J. Jacobs Award to honour outstanding achievements in research and practice relating to child and youth development.

And with the Jacobs Foundation Research Fellowship Program, it operates a global scholarship programme for research into the development, learning and living conditions of children and adolescents. It supports basic research and applied research alike.

‘We want to fund research in areas where there are gaps in knowledge,’ says Laura Metzger, co-lead of Learning Minds. To do so, the foundation turns to outstanding researchers who are the best in their field. Its academic agenda sees it advance the questions asked by the Jacobs Foundation. ‘Following a structured process, we set out the overarching topic, currently the variability of learning, and determine where knowledge is missing,’ says Metzger.

In addition, the Jacobs Research Fellows enjoy academic freedom. All kinds of insights have been gained in this way, but the Jacobs Foundation does not want to restrict itself to the support of cutting-edge researchers and is developing Strategy 2030. Nora Marketos, co-lead of Learning Schools, says: ‘We want to put the findings from this research into practice as evidence-based interventions, and contribute to systemic change as a result.’ Under this new strategy, the Jacobs Foundation will invest CHF 500 million in research and education by 2030. This will take place across various countries, with a special focus on the Ivory Coast, Switzerland and since the start of the year Ghana, as Marketos explains. The aim is to also add a South American country to the portfolio. In these countries, the foundation can draw on a network of partners and organisations working in close collaboration. Governments are also deeply involved. The World Bank is another key stakeholder, with this organisation active in the education sector in developing countries. The programme also encompasses NGOs, schools and private companies. This is exemplified by the programme TRECC, Transforming Education in Cocoa Communities. The Jacobs Foundation hopes to use this programme to enable people in the Ivory Coast to enjoy high quality education and contribute to educational change. ‘This programme shows that things work only through collaboration – and not without it,’ says Güntzer. And this is exactly where the new strategy is heading: the aim is collaboration between government, NGOs, foundations, local organisations, private individuals and industry.