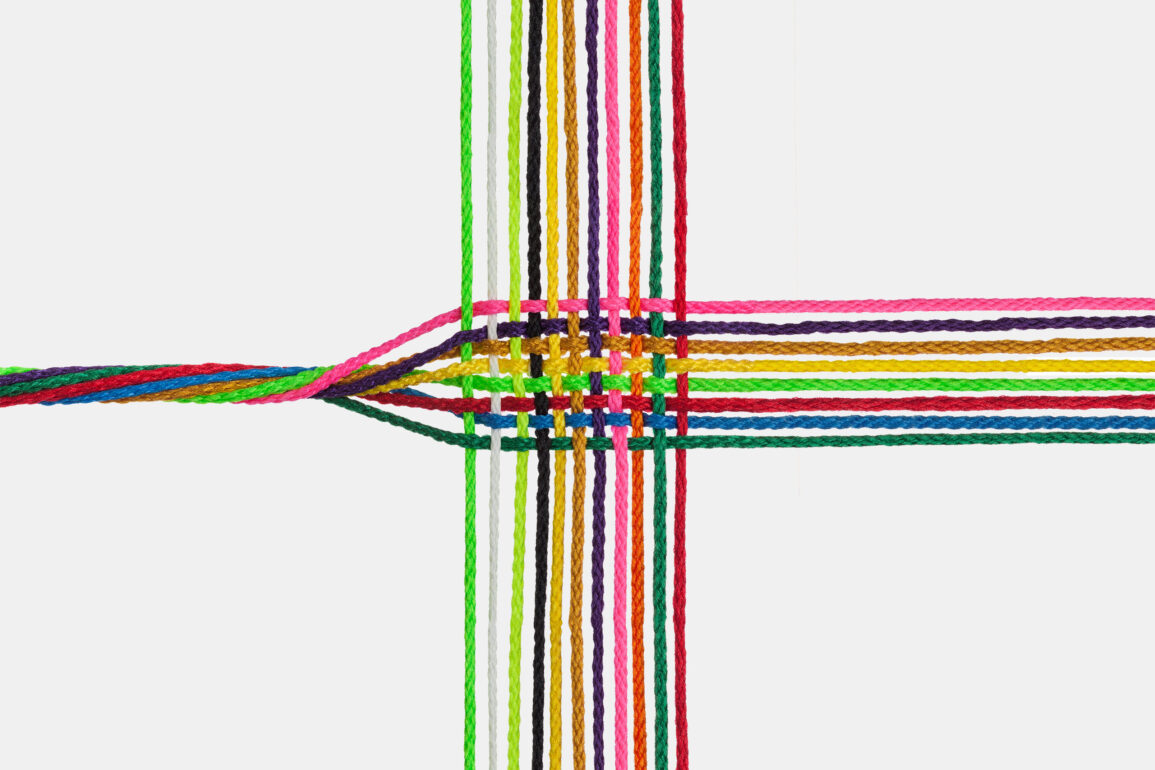

When different nonprofit organisations collaborate, their aim is usually to strengthen their impact and find a more effective way of achieving their shared goals. Collaboration brings more information and knowledge. At the same time, it increases complexity, as the organisations are shaped by very diverse cultures and have different resources and networks at their disposal. When gauging the right form of collaboration, there are various questions to be answered. Should decision-making powers be retained or not? Who is going to bear the financial risk? One organisation may opt to roll the project out itself, shoulder the financial risk and retain decision-making powers. Or several organisations may choose to cede both and look for a new sponsor organisation. And between these two options lie a range of different permutations. The human factor is always key to the success of the endeavour. Power struggles, hidden agendas or unvoiced assumptions can diminish or even thwart any impact. Conversely, it is the contacts that are made on an informal level that strengthen the collaboration. The additional benefits this brings extend beyond the boundaries of the actual collaboration itself.

Organised without a legal entity

‘It is an interesting new form of collaboration,’ comments Sabine Maier, director of Vivamos Mejor. In 2019, the NGO teamed up with five other Swiss aid organisations to found Alliance Sufosec. In that same year, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (DEZA) promised the prospect of programme contributions for alliances. As Sufosec, the six partners successfully applied for funding for a joint programme.

And DEZA recognised the alliance for 2023–2024 contributions, too. Collaboration between the members of the alliance is based on trust. This allows direct, straightforward communication among the organisations and open dialogue. The alliance is pursuing a common goal: to effectively fight malnutrition and hunger by strengthening sustainable, local food systems. The organisations are able to shine a stronger spotlight on the issue as an alliance and can learn from one another at the same time. For example, the alliance published a joint report on the hunger situation based on surveys of 14,000 households in 16 countries. Sufosec does not take the form of a legal entity. ‘At the moment, the organisational structure is very lean,’ Sabine Maier points out. Clear regulation, however, ensures that the members of the alliance hold equal status, despite their different sizes. All bear the same costs for the alliance’s joint activities. All have the same say. The model works well. The different ways the individual members of the alliance function is a challenge. However, the different perspectives are mutually beneficial. Legal and administrative factors mean that a legal entity could become a possibility in the future. But for now, the alliance is concentrating on fine-tuning its joint programme for 2025 and beyond.

Peer comparison

The practical aspects of the alliance’s collaboration are based on different models. When implementing their joint programme, when monitoring and learning from one another, collaboration is close. The organisations have set up a joint monitoring system, for example, complete with shared software. But even though there are projects involving joint fundraising, the individual organisations are still not collaborating much in this area. Each organisation also independently implements projects that contribute to the higher-level goals. ‘At the same time, there are several joint learning groups where we work on a particular issue together,’ Sabine Maier points out. The Steering Committee is in charge of strategic management, the Finance Group coordinates financial reporting, and the Programme Group discusses planning, monitoring and results. Sabine Maier sees this as a major benefit of collaboration. It means correlations can be drawn. The work of the individual organisations can now be compared in-depth with that of their peers. And joint surveys lead to a broader data basis with a more powerful information value.

Decentralised organisation

A shared level of knowledge and competency can form the actual goal of a collaboration. Specialists find their peers and learn from one another. The Swiss Life-Saving Association (SLRG), for example, communicates closely with partner organisations as a member organisation of the Swiss Red Cross. In turn, the SLRG is itself an umbrella organisation, made up of regional and local sections. Its role as an umbrella organisation implies higher-level status.

But the SLRG believes in self-management. ‘We don’t even have a hierarchical setup at the national offices,’ comments media spokesperson Christoph Merki. He describes its organisational model as a heterarchy – a decentralised model in which the various units of an organisation are not positioned above or below one another but are largely on an equal footing. He also points out that a mutual understanding of roles and a positive attitude towards collaboration are crucial to the success of this organisational format.

The SLRG encourages lateral dialogue between the sections and attaches importance to direct contact between the specialists. Different regional sections join forces and collaborate on operations too. Christoph Merki stresses the advantage of the independence of the sections. They can conduct their projects in an agile manner. ‘You don’t need everything to be controlled by headquarters. The channels are shorter.’ For collaboration to work, horizontal and vertical communication is important. Personal contact plays a key role in facilitating the flow of information. Independence also applies to financial resources. The umbrella organisation finances national campaigns and collects donations. But the sections have their own sources of finance too. The SLRG is also involved in international collaboration, for example with the International Life Saving Federation.

An alternative model

In the philanthropy sector, decisions on collaborative formats are usually guided by the objective. Working together towards shared goals should result in greater impact. An alternative option is the umbrella foundation. It reinforces the impact of each individual member independently. As a legal entity, the degree of formalisation is high. The administrative teams of the individual subfoundations or funds benefit from the use of synergies here.

Nine years ago, the Fontes-Stiftung transformed itself into the umbrella foundation Berner Dachstiftung. According to foundation board member Guido Albisetti, the move was triggered ten years ago, when the foundation began to receive increasing numbers of enquiries from smaller foundations whose assets were generating next to no return as a result of low interest rates. Income barely covered administrative costs. There were no resources left to fulfil the foundations’ aims. The umbrella foundation emerged as the ideal solution here.

Rather than creating a stream of new foundations, as in the past, the umbrella foundation allows Guido Albisetti to offer potential founders the opportunity to fulfil their aims while keeping administrative costs low. Shared management of assets allows costs for smaller assets to be kept to a minimum. This enables subfoundations or funds to generate income and make a philanthropic impact. A second reason was that many foundation board members are not keen on dealing with investment matters and are able to outsource them with this model. ‘We weren’t specifically looking to set up an umbrella foundation; we just wanted to find a way to help’, explains Guido Albisetti. For it to work, they defined the broadest possible nonprofit purpose for the umbrella foundation. This allows the subfoundations to be significantly independent in terms of their aims. The prospect of collaboration, though, remains unlikely. Guido Albisetti points out that the umbrella foundation specialises in background synergies that allow the funds and subfoundations to devote the majority of their resources to their charitable aims. Conversely, this means that the founders who turn to the umbrella foundation already have a clear idea of the cause they want to engage in.

Effort needs to pay off

Organisations can not only operate side by side, but also compete with each other. At the other end of the collaboration scale are partnerships with mutual organisation, resource management and strategic planning – and there are numerous levels in between. Complexity clearly increases in line with commitment. Partnership comes at a cost. It takes effort. As well as coordination and communication. But it also brings rewards that are well worth the effort. The Jacobs Foundation’s (JF) partnership initiatives strive to generate maximum added value, create alignment, and drive a shared vision for collective action.

Effective collaboration is most promising when partners have complementary expertise: “Our aim is to be creative partners and co-creators, supporting the development of new connections, networks, expertise and capacities. It’s important for us to work with partners who are clearly committed to sharing their knowledge and/or resources in a meaningful way,” says Donika Dimovska, Chief Knowledge Officer at the JF.

‘Our goal is to be creative partners and co-creators, supporting the development of new connections, networks, expertise and capacities.’

Donika Dimovska, Chief Knowledge Officer bei der Jacobs Foundation

Making transparent, collaborative decisions

As a thought leader, JF is involved in a wide range of partnership initiatives in focus countries and globally. Rather than adhering to a fixed collaborative approach, the foundation adapts its collaboration to fit the needs of the situation. However, the JF has clear procedures and processes for decision-making, implementation, and reporting, which must be transparent and, when necessary, collaborative. The JF can play various roles in a partnership, including that of a catalyst, inspiring others to transform the system as outlined in its Theory of Change. The foundation’s objective is to provide added value in a partnership by bringing together key interest groups from within government, the private sector, academia, and civil society. The JF aims to mobilize the use of evidence to strengthen learning ecosystems in partner countries and inspire systems change beyond its reach. “The key to success is aligning around shared objectives and incentives and bringing parties that do not typically come together to the table. If the objectives and/or expectations are too diverse, it can be difficult to establish a successful partnership,” says Donika Dimovska.