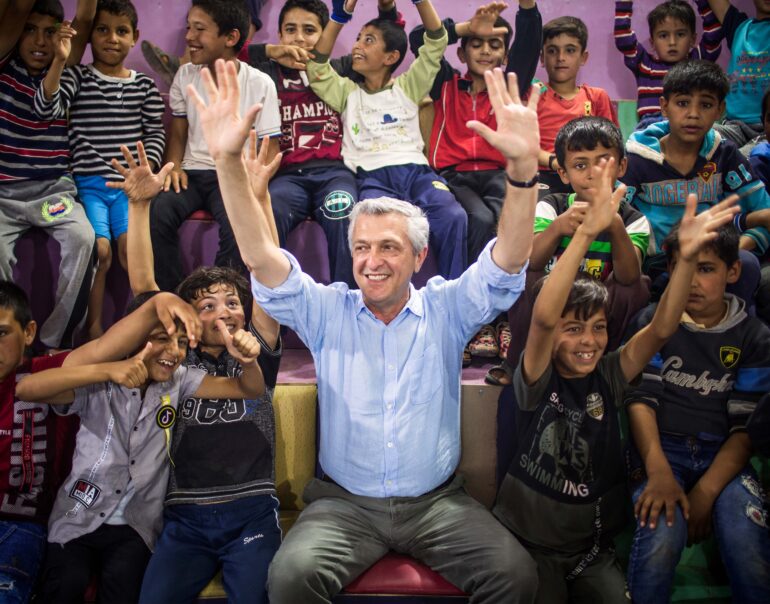

Being able to help people in dire situations is the force that drives him. Filippo Grandi, the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees, has devoted his whole life to supporting refugees.

The Philanthropist: You have been working with refugees for more than 30 years…

Filippo Grandi: …almost 40…

…in all these years, have you ever faced a situation where you told yourself you just could not do it anymore?

Challenging moments do crop up time and again. Actually, every day. But then I go to bed and I wake up to a new day and new beginnings.

The increasing number of refugees and displaced people must keep you very busy, right?

The number of people who have been forced to leave their home has sharply increased over the last few years. Today, more than 82 million people have either had to leave their country or flee within their own country. That number has continued rising over the past 10 years. I

We’ve heard you say that we should not wonder if we’ll one day reach 100 million displaced people worldwide, but rather when we’ll reach that number…

“100 million” is a striking figure. However, 82 million is already very bad – especially when you realize that this figure was just half of that a few years ago.

So, this number will continue to rise?

Yes, unless we put an end to the current wars around the world. To accomplish that, many of the powerful nations in the world will have to work together. Today, that is not the case. And if we do not address the current huge challenges like climate change and poverty as a united front, which again is not the case, I do not see how that number can go down.

Were we resolving them before?

In the 90s, we had crises such as Yugoslavia and Rwanda. We entered into negotiations to find solutions, and many people were ultimately able to go home. Such solutions are not on the table today.

How were things different back then?

After World War 2, lots of wars broke out on a local scale. The major powers of the time, the US and the Soviet Union, fought many proxy wars. When the Berlin Wall fell, the world changed and we stepped into an era with the potential for all kinds of solutions: it was a messy time full of crises, but we always managed to find solutions.

Why have things changed since then?

The geopolitical situation was impacted by three major events: 9/11, which triggered a climate of fear. Then, about a decade ago, there was the financial crisis. Global power shifted, and the world grew into a multipolar system in which even medium-sized and small States have influence. Today, we are in a transition phase towards a balance of power, but we are not there yet. We are seeing many complicated wars and complex situations.

On top of that, we have a new battlefield of disinformation war. Unscrupulous politicians use digital communication to spark fear; they claim that the people who come to your country want your jobs, threaten the values you cherish, and put your safety at risk. This narrative is quite prevalent and very common, and can win elections. The tragedy is that it has tremendously weakened people’s feelings of solidarity towards others.

Does this have a direct impact on your work?

UNHCR is an organization of member States, not an NGO. We need the citizens of those member States to help uphold the principles of human rights and justice — to call on their governments to help refugees and displaced people.

It’s even taken Europe a long time to find solutions…

Europe is in a unique situation. The issue of refugees overlaps with the challenges faced by the European Union of migrant influx. EU Nations must work together. People will always come to Europe: people have been moving to Europe for centuries and that won’t change. Europe is wealthy, which makes it an attractive destination; and there is peace in Europe, which is appealing to migrants. But refugees — people forced to flee — are driven by life threatening circumstances. Walls are not the answer. Notwithstanding the ethical issue they raise, they simply don’t work. Countries need to stand together and resolve conflicts. It’s hard, but it’s not impossible. There are 27 EU-countries, plus Norway, the UK and Switzerland.

Photos: UNHCR/Diego Ibarra Sánchez

‘Helping people going through terrible situations is the most important mission we have.’

Filippo Grandi

What can the Swiss philanthropic sector do to help?

Provide resources, donate, be philanthropic in the traditional sense. But we also need authentic partnerships, in which we work together to solve a problem. Obviously, technology has become one of the most exciting areas for collaboration; I see many ways to get involved here. But sustainable energy and climate change are also in our line of sight.

How so?

The link between climate change and migration is very intricate. We must fight climate change and also reduce our own carbon footprint. There’s no doubt that the private sector is the best sector to partner with here.

Are you reaching out to the corporate sector?

Yes, but not only. By ‘private sector’, I mean companies and individuals. While States will continue to be our main donors, to date, we have three million donors, including private sector partners, foundations and individuals, which is a lot, but it’s also frustrating because we could do more. Most of the time, we work with countries. There can be a lot of red tape and the governments are often, naturally, driven by their own interests. That’s why I’m always very happy when we can build a relationship with the philanthropic sector. Foundations and individuals understand that coming up with solutions involves true philanthropy, and not only self-interest. That’s very refreshing.

The refugee situation is becoming increasingly complex. Will your work become more complex too, in a positive sense?

While I love complexity, there is nothing positive about this kind of complexity. It’s always a challenge. If anyone today says the situation is easy to solve, they are either a populist or they are wrong. I do not wish to be either. However, I am cautiously optimistic that in these challenges lie opportunities to partner creatively, innovate and adapt, and thereby, change the way we continue to tackle these problems.

COVID-19 has not made life easier. The vaccines have been disproportionally distributed over the world.

Vaccine equity remains a global challenge, but there is hope. Uganda is a good example: it’s a very generous nation towards refugees, offering a home to 1.5 million people from South Sudan, the Congo and other conflict-stricken regions. Uganda gives these people land, access to the labour market and additional services. It’s a poor country that displays great generosity, which much richer nations have failed to match. I’m not saying that everything’s perfect in Uganda, but you asked about vaccines. I was there in the spring, and the local authorities explained that if they had had enough doses, they would have already finished vaccinating everyone, including refugees. Their plans include refugees! But because they have very few vaccines, their schools, among other things, are still closed. In Europe, about 62% of people have been vaccinated, but there are countries in Africa where it’s less than 10%. Of course, there are countries such as the US who are sending vaccines to developing countries, but that’s not enough. When I hear that our fridges are full of vaccines that people do not want, it makes me pause.

Is there a solution?

Yes, but only one: wealthy countries must send more doses to poorer countries. When the pandemic is over, we will need to identify the reasons behind this distribution inequality.

What is UNHCR doing?

We do not distribute vaccines ourselves, but we have strongly advocated for inclusion of refugees in national vaccine rollouts through GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance. Among other things, we have worked with refugee communities to educate on contagion and implement social distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, including the distribution of hand sanitizer and masks. We needed a lot of funding to carry out all our efforts worldwide, and people heard us. But since then, the philanthropic urge has somewhat wavered. We are struggling to communicate that we still need large amounts of funding; however, the crisis is not quite as visible today.

Could it be that we have gotten used to it?

Yes, it could be. We need a lot of help from the private sector, from public authorities and businesses, in particular regarding prevention, hygiene and logistics.

COVID-19 was a crippling layer to severely compromised communities. What are the most challenging humanitarian situations at present?

It’s hard to say. This summer, Afghanistan was undoubtedly the biggest crisis. It’s a devastating and tragic situation. When the Taliban took over the government, many people feared the worst. The world was focused on the evacuations, but a big crisis loomed in country, where some 700,000 people have been displaced since the beginning of the year. There wasn’t the mass movement or exodus people were expecting across borders. If the country doesn’t recover economically, and if security and stability remain precarious, there could well be a bigger refugee crisis and the situation will be worse than in 2015/16. And we should not forget that the Afghan people need help, even without any new displacements.

Photo: UNHCR/Diego Ibarra Sánchez

What’s the situation like in Afghanistan?

There are already millions of refugees in neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and others. The number of displaced people within Afghanistan is also huge: these past few months, hundreds of thousands more have been added to the 3.5 million who have had to leave their homes over four decades of protracted conflict. If we do not want them to become refugees as well, we need to help them now, so that they can return home. The current stability is very fragile. The people who depend the most on aid are either in country or in refugee camps along the borders. It’s a complicated situation to get across to the public. During the summer, people were aware and concerned about the situation, and we received proportionately large donations: in the first three weeks, we raised USD 20 million from private donors and companies.

Has the concern waned?

Yes. And here is the difficult part: while the media spends less time reporting on this crisis, winter is around the corner. The people need to be protected (from the cold) with blankets and other basic items.

Is there a solution?

When humanitarian disasters of this scale occur, the world typically rallies. Even the Taliban want to help the refugees, there’s no doubt about it. I was there and I spoke to them. We are focusing on how we can help displaced people through the winter, and provide them with shelter, protection, tents and so on. UN aid agencies have an efficient and operational network in Afghanistan. We have space to provide aid, but we need the resources.

Children are particularly exposed. What message of hope do you have for children who are born as refugees in a crisis like this one?

It’s important that refugees are given access to education. This topic, which has gained momentum, was sparked by the Syrian crisis. When Syrian refugees were asked what the reasons were for fleeing their country, they answered the challenging life-conditions, the food shortages, and also the fact that their children were not able to go to school. This showed people in wealthy countries that education for refugees is an absolute necessity, and there’s been some real changes in that regard. About six years ago, just 50% of refugee children attended primary school. The global average for non-refugee children is almost 90%. Targeted programmes have enabled us to improve refugee children’s access to education from 60% to 70%. Progress which was drastically undermined during the pandemic.

What gives you the assurance that what you do is making a difference and is helping people?

I am an optimist. When I meet with people forced to flee, I see in many their indomitable spirit; they have witnessed the worst of humanity, but when someone can show you compassion, believes in you, stands up for you and with you – that solidarity can make all the difference.

I mean, given all the negative and sad things you’ve mentioned...

Well let’s talk about the ‘Global compact for refugees’ initiative for instance. This framework contains goals for climate change, education and other important issues. It’s really a kind of toolbox full of ideas, an invitation for everyone who can and wants to help. The participating UN States approved the content together, but it’s not targeted at States alone. It’s crucial as a tool for civil society and for the business, cultural and sporting sectors. The fact that all the States agreed to the framework is encouraging and gives us hope. Helping people going through terrible situations is the most important mission we have. I believe this – and I have always believed it.